A Loophole that Effectively Legalizes Most Crime in Seattle

ANALYSIS OF SEATTLE CITY COUNCIL PROPOSAL TO EXCUSE AND DISMISS MOST MISDEMEANOR CRIMES

By Scott Lindsay – attorney; Seattle resident; former public safety advisor and special assistant for police reform to the City of Seattle; former senior counsel to House Oversight Committee Democrats.

On Wednesday, October 21, Councilmember Lisa Herbold, chairperson of the Seattle City Council’s Public Safety Committee, introduced far-reaching legislation to excuse and dismiss almost all misdemeanor crimes committed in Seattle by persons with symptoms of addiction or mental disorder. Any perpetrator with a credible claim of behavioral health symptoms – anything from drug use to depression – would effectively have blanket immunity from prosecution for misdemeanor assault, theft, harassment, trespass, stalking, car prowl, and 100 other Seattle criminal laws.

Councilmember Herbold’s proposal would create a legal loophole that would open the floodgates to crime in Seattle, effectively nullifying the city’s ability to protect persons and property from most misdemeanor crimes.

You may be thinking, this sounds like hyperbole. Sadly, it is not. The legislation, analyzed in detail below, provides an absolute defense – meaning the defendant cannot be convicted and the case must be dismissed – to all non-DUI/domestic violence (DV) misdemeanor crimes in any of three circumstances:

- Substance use disorder – if the defendant can show “symptoms of” a substance use disorder (e.g., drug or alcohol addiction) (note: the defendant need only show symptoms, not a medical diagnosis);

- Mental disorder – if the defendant can show “symptoms of” a mental disorder, defined broadly as “any organic, mental, or emotional impairment which has substantial adverse effects on a person’s cognitive or volitional functions” (e.g., depression, anxiety, etc.); or

- Poverty – if the defendant can show they committed the offense to meet “an immediate basic need related to an adequate standard of living for the actor and/or other family” (e.g., stole merchandise in order to sell for cash the defendant claims would be used to meet a basic need).

According to Councilmember Herbold’s legislation, over 60 percent of Seattle misdemeanor defendants have substance use or mental disorders and 90 percent are considered indigent. But even those numbers undercount the number of defendants that would qualify for the defense. In order to have their case dismissed, defendants would not need to prove they had symptoms of a behavioral health disorder – a de minimis threshold to satisfy that would be almost impossible for prosecutors to rebut.

Last year, Seattle Police made approximately 12,000 non-DUI/DV misdemeanor arrests (two-thirds of all SPD arrests). The City Attorney charged 5,421 of those cases in Seattle Municipal Court (the rest were declined by the City Attorney for a variety of reasons). The 2019 charged cases included 1,850 theft cases, 1,345 assault cases, 816 trespass cases, and 473 harassment cases. In total, last year, Seattle Municipal Court saw cases charged under 108 different Seattle criminal codes (e.g., stalking, cyberstalking, sexual exploitation, animal abuse, unlawful carrying of a pistol, indecent exposure, etc.).

So why haven’t you heard about this City Council proposal to radically rewrite Seattle’s most basic criminal laws? The reason is because Councilmember Herbold bypassed the regular legislative procedure for consideration of changes to the substantive laws of the city at the request of the public defenders who drafted this proposed legislation. Councilmember Herbold did not introduce the legislation in her own Public Safety Committee. City Council has never held a public hearing on it. The legislation was never made readily accessible to the public. Instead, it was introduced through a backdoor: as an amendment in a Budget Committee meeting to discuss community safety and violence prevention programs.

Under the Council’s own rules, the Budget Committee, chaired by Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda, is only supposed to consider funding questions such as how much to spend on each department and program. But at this hearing, Budget Chair Mosqueda helped Public Safety Chair Herbold bypass the regular legislative process, claiming the legislation is appropriate for the budget because it would dramatically cut the city’s jail costs – if less people can be prosecuted then few will go to jail, saving the city money, or so the argument goes.

This maneuver to evade the regular legislative process has kept the proposed legislation almost entirely hidden from the public. Indeed, the legislation is not currently available on the Council’s or City Clerk’s website and there was no media coverage except for one paragraph at the bottom of a Seattle Times procedural article on the police budget.

Because the legislation was only discussed for five minutes after almost three hours of a hearing that was supposed to be on funding questions around community safety and violence prevention programs, none of the other news outlets that closely scrutinize Council actions covered it.

Two days after the hearing, neither the Seattle Police Department nor Seattle Municipal Court were even aware that Councilmember Herbold – the Chairperson of the Council’s Public Safety Committee, former chair of the Budget Committee, and a 20+ year City Hall insider – had introduced a budget amendment that would negate the majority of Seattle’s criminal code. I do not know if anyone at Council consulted with the City Attorney’s Office before introducing the legislation.

The reason major legislation changing the substantive laws of the city is not supposed to be allowed in the budget deliberations is because that process is truncated and often opaque. Within a two-month span, Council considers funding questions for every department and function of the city. From today, there is only one public comment period before Budget Committee Chairperson Mosqueda releases her consolidated budget on November 10. The Council is scheduled to vote on its final budget package on November 23.

Below is a closer look at: (1) how the proposed legislation was introduced; (2) what it says; (3) the impact it would have on public safety and Seattle’s criminal justice system; and (4) a brief conclusion.

An important note: the backdoor introduction of this proposed legislation happens to coincide with the last two weeks of the most hyper-partisan, polarized election in modern history. If you are viewing this with the hope of finding some ‘red vs. blue’ wedge issue, STOP! Dyed-in-the-wool blue Democrats like me are out here fighting every day to keep Seattle one of the most successful, progressive, and beautiful cities on earth. Public safety for the entire community is critical to Seattle’s economic and social recovery.

1. Backdoor legislative process

The legislation was introduced at a Council budget hearing on “Community Safety and Violence Prevention,” on Wednesday, Oct. 21. All councilmembers were present (via videoconference) for the hearing. Councilmember Herbold’s proposal was the first item to be considered in the discussion and was previewed in the Council central staff memo and presentation that accompanied the hearing (excerpt of the staff memo, pg. 13, and accompanying presentation):

Discussion of the amendment began at hour 2:50 and lasted only five minutes:

After Council staff gave brief background on the legislation, Councilmember Herbold stated:

- “Community is asking that the Council consider this to be budget legislation and I am putting it forward in that spirit in the hopes that my colleagues agree that because of the potential impacts that it might have – legislation like this to our budget – that we do consider it budget legislation.”

- “90 percent of cases prosecuted by the city – in those cases the individual charged is represented by a public defender because the individual is indigent.”

- “[The Seattle Reentry Workgroup] final report found that poverty, institutionalized racism, and systemic oppression are root causes that lead to mass incarceration. And they found that punishment and incarceration are harmful and ineffective tools to address behaviors triggered by poverty and illness.”

- “[The Reentry Workgroup recommended that the city] instead develop responses that do not burden individuals with criminal history or the trauma of incarceration.”

- “The link to the budget process is really bound in the negotiations that will be going on over the next several months into next year regarding jail usage. This is unknown right now but the idea being that by providing this defense to individuals it may result in even less reliance on the jail and might conceivably have some impacts on the jail contract.”

After Councilmember Herbold introduced the legislation, Budget Chair Mosqueda asked if there were any questions from other councilmembers. There were none. Chairperson Mosqueda then confirmed the supposed budget linkage was that the City would save money by reducing jail usage with fewer prosecutions of Seattle’s criminal code.

As noted by Councilmember Herbold, the idea to effectively halt most misdemeanor prosecutions originated from a relatively obscure report issued by the Seattle Reentry Workgroup. In 2015, this group was created by Council under the umbrella of the Seattle Office of Civil Rights with a relatively narrow mandate to review and make proposals for improving how prisoner reentry following incarceration. The final report, issued in October 2018, went much, much further: recommending massive investments in housing for formerly incarcerated persons and the cessation of almost all misdemeanor prosecutions.

As noted by Councilmember Herbold, the idea to effectively halt most misdemeanor prosecutions originated from a relatively obscure report issued by the Seattle Reentry Workgroup. In 2015, this group was created by Council under the umbrella of the Seattle Office of Civil Rights with a relatively narrow mandate to review and make proposals for improving how prisoner reentry following incarceration. The final report, issued in October 2018, went much, much further: recommending massive investments in housing for formerly incarcerated persons and the cessation of almost all misdemeanor prosecutions.

The legislation introduced by Councilmember Herbold was apparently drafted by the King County Department of Public Defense (DPD). Seattle contracts with King County for indigent misdemeanor defense and so DPD attorneys are the ones that represent virtually all of the defendants that would be impacted by this legislation. In fact, the DPD website is the only place where, as of October 26, the public can currently find the legislation introduced at Council.

Notably, Councilmember Herbold stated in her introduction of the legislation that “Community is asking that the Council consider this to be budget legislation.” But nowhere have the principal organizations that have been leading calls for defunding the police and other major policy changes requested or even mentioned this proposed legislation or the concept behind it.

2. Blanket immunity from most misdemeanors

Under the Seattle Municipal Code, defendants have three legal defenses separate from the factual defenses of whether they committed the alleged crime: (1) insanity (the defendant could not understand the consequences of their actions); (2) entrapment (law enforcement induced the defendant to commit the crime); and (3) duress (someone forced the defendant to commit the crime by threatening bodily injury). If the defendant can show that one of these defenses apply, the case must be dismissed.

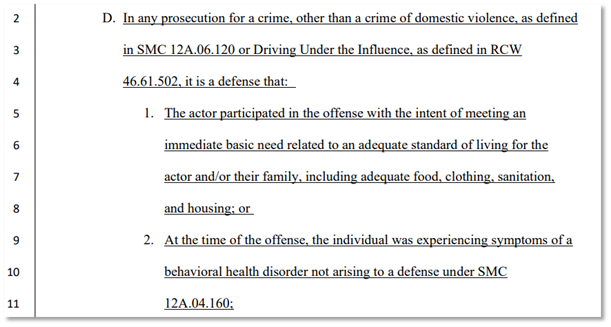

The legislation introduced by Councilmember Herbold would add three additional defenses for defendants (framed in the drafting as two defenses). The legislation states:

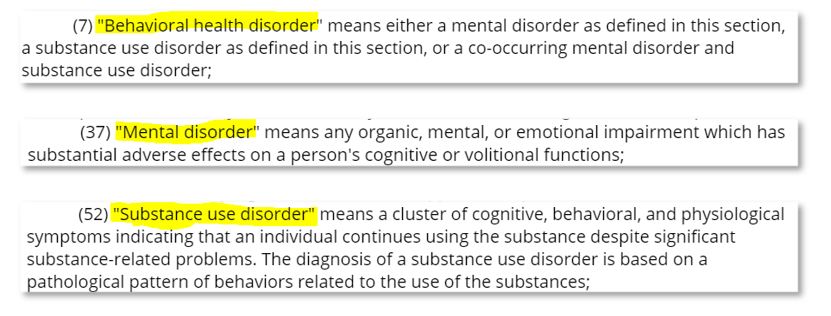

The legislation includes definitions that link to the mental health provisions of the Revised Code of Washington:

While the legislation is framed as simply adding to the duress defense, the actual proposed defenses have no real relationship to duress as it is narrowly defined in the Seattle Municipal Code or understood in the common law (the duress defense is rarely raised and almost never successful). In addition, while the drafters of the legislation lead with the so-called ‘poverty defense,’ the behavioral health disorder (substance use disorder or mental disorder) defense sets a much lower burden for defendants and would therefore be the defenses most commonly used.

Here’s what the proposed defenses would look like in practice:

- Substance use disorder – Any (non-DUI/DV) misdemeanor case must be dismissed if the defendant can show “symptoms of” a substance use disorder. The defendant must only show that they use substances “despite significant substance-related problems.” Given that the defendant is already facing criminal charges, a defendant would only need to claim drug or alcohol addiction to satisfy his or her burden on a preponderance of the evidence standard. There are few practical ways for a prosecutor to disprove someone’s claim that they are experiencing symptoms of a substance use disorder to drugs or alcohol.

- Mental disorder – Any (non-DUI/DV) misdemeanor case must be dismissed if the defendant can show “symptoms of” “any organic, mental, or emotional impairment which has substantial adverse effects on a person’s cognitive or volitional functions.” According to the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-5, major types of mental disorders include: anxiety, ADHD, depression, PTSD, bipolar disorder, among others. Again, there is no practical way for a prosecutor to disprove a defendant’s claim that they are experiencing symptoms of a mental disorder. (Note: the proposed mental disorder defense has little relationship to the insanity defense which requires very specific psychiatric analysis of the defendant’s mental state. Very few individuals who have mental disorders meet the very high ‘insanity’ defense threshold).

- Poverty – Any (non-DUI/DV) misdemeanor case must be dismissed if the defendant can show they “participated in the offense with the intent of meeting an immediate basic need related to an adequate standard of living for the actor and/or other family,” with basic need defined as including but not being limited to food, shelter, clothing, medical care, and sanitation. This defense presents a modestly higher standard than the first two defenses because here the defendant must show some nexus between the alleged crime and a basic need.

While the ‘poverty defense’ would almost never actually be deployed given the de minimis threshold for most defendants to meet the other two defenses, on paper it would negate most theft prosecutions, even thefts of commodities that themselves are not basic needs. For example, if a defendant stole $500 worth of merchandise from a downtown retailer with the intent of selling them to a fence on 3rd Avenue for $75 cash, the defendant would only need to claim that his or her intent was to use the money to buy food in order to satisfy the “basic need” nexus. Even if the defendant told police post-Miranda that he/she intended to use the proceeds from the stolen goods to buy drugs, the defendant’s public defender would argue that drugs are a “basic need” for someone with a substance use disorder.

The standard to satisfy either of the two “symptoms of behavioral health disorder” defenses is so low, it is euphemistic to call them defenses. For all practical purposes, this legislation would provide blanket immunity from misdemeanor prosecution for virtually all non-DUI/DV defendants. Any credible claim of anxiety, depression, trauma, or addiction would make the defendant un-prosecutable for the vast majority of crimes in the Seattle Municipal Code, no matter how many times the defendant had committed the crime or how egregious the circumstances.

3. Negative impacts on public safety and criminal justice

Seattle has over 100 misdemeanor criminal laws in the Seattle Municipal Code, excluding DUI and DV offenses. Misdemeanors are any crime subject to one year or less in jail and are prosecuted by the Seattle City Attorney in Seattle Municipal Court. (Felony offenses are crimes subject more than one year in jail that are encoded in the Revised Code of Washington and prosecuted by the King County Prosecutor in King County Superior Court).

Enforcement of Seattle’s misdemeanor laws is the bulk of the work performed by the Seattle Police Department and non-DUI/DV misdemeanors represent almost half of all the criminal activity interdicted by officers every year. In 2019, Seattle Police made an arrest or requested charges against a suspect in approximately 12,000 total non-DUI/DV misdemeanor cases. The City Attorney filed charges in 5,421 non-DUI/DV cases in Seattle Municipal Court in 2019. (The remaining cases are declined for a variety of policy, administrative, or evidentiary reasons, an issue I examined in the second System Failure report).

The most common misdemeanor offenses in Seattle are theft, assault, trespass, harassment, and property destruction. Below is a partial list of the most common misdemeanor crimes and the number of cases filed in 2019:

In 2019, I authored a report entitled System Failure: Report on Prolific Offenders in Seattle’s Criminal Justice System which examined 100 prolific offenders who had repeatedly cycled in and out of jail, mostly on misdemeanor charges. The main findings of that report were that all of the non-DUI/DV offenders with the largest number of cases (often 10 or more arrests per year) were suffering from substance use disorders and homelessness and that these individuals had repeatedly committed the same crimes in Seattle’s busiest neighborhoods.

For example, Steven R. is a 36-year old white male with 44 misdemeanor cases in Seattle Municipal Court and over 100 criminal cases in Washington state. The City Attorney’s Office filed 11 cases against him in October of 2020 alone (see below). According to court records, he suffers from substance use disorders, mental health conditions, and is homeless.

Steven creates large disturbances in retail establishments, including threats, harassment, and assaults of retail employees. For example, in 2018, Steven terrorized a downtown Bartell Drugs, threatening staff, telling them he had a knife, and leading officers on a chase through the downtown core.

Steven had 11 bookings into jail in the past year, most recently two days ago. Under Councilmember Herbold’s proposed legislation, because of his history of substance use disorders and mental health conditions, he could not be prosecuted for any of his most recent misdemeanor offenses in Seattle.

4. Conclusion: accountability with social services

Seattle’s criminal justice system is broken. Prolific offenders cycle from jail to the streets and back without any meaningful effort to address their behavioral health disorders. I share common cause with Councilmember Herbold and the public defenders in that belief. Everyone deserves to be frustrated.

But the answer is not to throw out Seattle’s only means of accountability or disruption for misdemeanor crime. That path would be catastrophic for Seattle’s residents, businesses, and visitors. And it would only enable the destructive behaviors that are already ruining the lives of individuals committing frequent misdemeanor crimes.

Seattle and King County should instead be focused on building robust behavioral health interventions into the criminal justice system. The public needs protection from Steven. And Steven needs in-patient treatment help for his addictions and mental disorders. But he cannot be trusted to get it on his own volition. Neither the public’s interests nor Steven’s would be served by turning a blind eye to his criminal activity.