What’s really behind the record number of homeless deaths?

July 6, 2022

Last week we took aim at claims made by sources in a Seattle Times story that the removal of drug camps was driving homelessness deaths. We’re now going to look at one of the actual problems.

Drug overdoses.

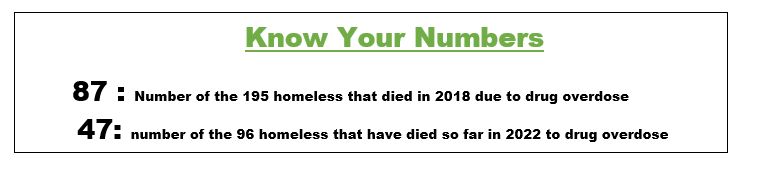

The homelessness problem in Seattle is primarily a substance addiction problem. Of the 195 homeless that died in King County in 2018, the highest ever, 87 of them died from drug overdoses. Of the estimated 96 homeless people who have already died so far this year, 47 have been from a drug overdose.

Of course, we don’t know how accurate those figures are because, as The Times reported, the county doesn’t keep track of homeless who’ve died in hospitals. That means if a homeless person suffering an overdose is transported to a hospital and dies, it’s not considered a “homeless death.”

But that’s just one of many dysfunctional policies that existed already – and it could get even worse.

The primary cause of drug overdose deaths among the homeless is fentanyl. We can debate how to deal with drug addicted homeless who refuse shelter or services. But one thing that is definitely NOT the solution is to indulge them, at taxpayer expense.

But that is what some sources cited by The Seattle Times actually argue.

Brad Finegood is a strategic adviser for Public Health Seattle & King County. He told The Times that “people should not use (fentanyl) alone, and people should have naloxone on them,” which counteracts the effects of an overdose.

Is this an official policy position for the city and King County? Use drugs, just make sure that you’re not alone when you do it and have a way to reverse an overdose if you have one? How about telling them to seek treatment so they can sober up before they die of an overdose?

The Seattle Times then quotes a homeless man who said “governments should stock naloxone in places like buses and trains and public restrooms, and people should be aware of overdose symptoms like pale, blue skin, shallow breathing or choking or limpness.”

The fact is most of these people don’t want to get off the street and they don’t want to sober up. They are so addicted they will refuse help. As doctors operating out of neighborhoods like Ballard can tell you, when they arrive to help a homeless person suffering from a drug overdose, the homeless expect them to hand over naloxone and then leave.

The reality about addiction is that no one can compel an addict to recover. They have to decide to do that themselves. The public is not there to enable their lifestyles, but to help those who want to change. Yet what we’re currently doing now is enabling their habits.

If you think the situation is bad now, it will get infinitely worse if Initiative 1922 qualifies and is approved by voters this fall. The initiative decriminalizes street possession of fentanyl, cocaine, and heroin in the entire state. However, we can fully expect the brunt of the policies to fall on Seattle and King County.

Our laws aren’t enforced as it is, but this will make it an official rather than unofficial policy. It will attract more drug addicts from other parts of the country, who will inevitably add to the number of homeless deaths. That’s precisely what happened in Oregon, where drug overdose deaths increased by 41 percent between 2020-2021 after voters enacted a measure similar to I-1922 in 2020.

Rather than admit to a mistake, the usual suspects behind these proposals will claim a worsening crisis is further proof that we need to spend more taxpayer money on fighting homelessness.

But as we’ll be exploring in a future piece, there’s already plenty of money to go around. How it’s being spent, though…

Stay tuned.