Mayor Bruce Harrell’s homelessness plan needs work

Earlier this year we wrote about how King County’s previous efforts to eliminate homelessness failed because those involved incorrectly diagnosed the root problem, warning that any future attempts to address the crisis needed to attack the real causes – substance abuse and mental illness.

Unfortunately, Mayor Bruce Harrell appears to be making many of the same mistakes.

Last week Harrell unveiled his Homelessness Action Plan that includes $118 million in spending within the King County Regional Homeless Authority (KCRHA).

In short, there’s a lot to be concerned about.

The biggest issue is that, like his predecessors, Harrell’s plan is founded on the erroneous belief that housing unaffordability is causing people to become homeless. We’ve argued in the past that when ordinary people can’t afford to live somewhere, they move to where it’s more affordable. People with severe mental health issues and addictions don’t move because they aren’t capable of taking care of themselves, which is why they end up homeless.

Make Your Voice Heard!

Contact Mayor Harrell’s office , thank him for removing the homeless encampments and encourage him to address addiction and mental health in his Action Plan.

Harrell’s plan puts the cart before the horse:

Homelessness can result in physical and mental health challenges including addiction, as well as be the outcome of those health challenges. The longer people remain unsheltered, the more likely they are to need help. To break this cycle, we must act with urgency to bring people indoors and provide health services.

This is confusing the cause with the symptom. Coughs don’t cause colds, but people with coughs have colds. Homelessness doesn’t result in mental health and addiction, it is driven by it. Seattle’s housing unaffordability is a problem, but that is causing people to leave the region. However, the regional mental health crisis is pushing more people onto the streets.

To be fair, there’s parts of Harrell’s plan that are good, including a homeless dashboard that provides the location of encampments and RVs, among other things. His plan also states that “we have an obligation to ensure open, clean, and accessible public spaces like parks, rights-of-way, and sidewalks.” Much of the $118 million for KCRHA is to provide those homeless with 1,300 new shelters housing, rather than occupying spaces meant for the general public.

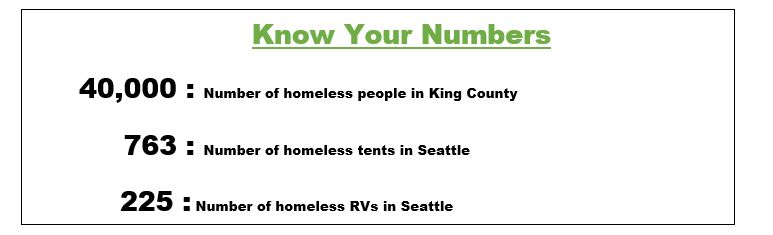

Since a homelessness crisis in the city was declared in 2015, the problem has only gotten worse. According to King County, there are more than 40,000 homeless people in the region. In contrast, the city of San Francisco has 874,784 residents, yet only 4,397 homeless people, and that figure represents a decrease from prior years. New York City has 50,000 homeless people, but its population of 8.38 million dwarfs that of Seattle and King County combined.

Seattle needs a plan on how to fix this.

But not acknowledging mental health and drug addiction as the primary causes is why previous efforts to address homelessness failed spectacularly. Throwing money at shelters as a long-term solution doesn’t work. And frankly, at this point Seattle residents have good reason to be skeptical of new spending. What accountability measures will there be for that new spending? If the plan fails to meet its goals or reduce the homeless population, who will be held accountable?

Better yet, is there anyone involved who directly or indirectly benefits even if the plan fails?

Let’s also not put too much trust, let alone $118 million, in the King County Regional Homeless Authority. The agency’s own website says that “it is possible to end homelessness.”

No one who is serious about the problem believes this. Director of All Home King County Mark Putnam admitted that their own goal set in 2005 to eliminate homelessness “had been unrealistic, as the reality is that no community has ever been able to achieve 0% homelessness.”

The homeless authority also states on its website that “homelessness can happen to anyone.”

Again, no serious person thinks this. But these unserious people are the ones who still get public tax dollars, and we wonder why nothing gets done.

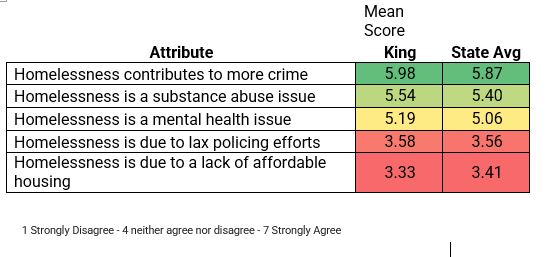

People in King County understand this better than other Washington residents. According to a survey of 3,000 people conducted by Unleash Wa between January-February 2022, the average King County residents agreed more often and more strongly with the belief that homelessness is a substance abuse and mental health issue than the average person polled from other areas in Washington.

If Harrell is actually serious about addressing homelessness, he needs more than realistic goals. He needs to focus on mental health and substance abuse. He needs to acknowledge that there are some people who, for one reason or another, are fundamentally incapable of caring for themselves and that’s why they end up homeless. For their wellbeing and that of society’s, they need to be provided long-term housing facilities where properly-trained professionals, not amateur activists or utopian nonprofits, are attending to their needs while being held accountable in a transparent manner.

Instead, for years we’ve had a dysfunctional nightmare that has drawn national attention. Millions of taxpayer dollars have been doled out to various groups with no accountability for how the money is spent and no meaningful goals set. Meanwhile the number of homeless have grown while activists have vehemently fought to keep these vulnerable people in unsanitary, unsafe living conditions.

Harrell so far has lived up to his word on cleaning up homeless encampments, and he is correct that these people need somewhere else to live. But the permanent solution is not temporary housing or shelters.

While the city’s $173 million homelessness budget for 2022 doesn’t dedicate any money specifically for mental health, the fact is that this is indeed a problem that goes beyond the city. It is a regional one, and it needs regional solutions.

As we’ve said before, you can’t fix a problem if you don’t understand what’s causing it.

If Harrell wants to avoid to another failed fix, he needs to rework his plan before he implements it.

Contact Mayor Harrell’s office and tell him that his Action Plan is a fine start but it needs to address mental health and drug addiction.